A sound investment strategy starts with an asset allocation that is built upon reasonable expectations for risk and returns and uses diversified investments to avoid exposure to unnecessary risks, as outlined in Vanguard’s Framework for Constructing Globally Diversified Portfolios.

Most investment portfolios are designed to meet a specific future financial need – either a single goal or a multifaceted set of objectives. To best meet that need, the investor must adopt a disciplined method of portfolio construction that balances the potential risks and returns of various types of investments.

Although no one can predict which individual investments will do best in the future, we believe the best strategy for long-term success is to have a well-thought-out plan with an emphasis on balance and diversification and a focus on keeping costs low and maintaining discipline.

This article discusses how to create and maintain a diversified portfolio by focusing on five major components:

Defining investment goals and constraints and the importance of a sound investment plan.

Broad strategic allocation among the primary asset classes such as equities, fixed income and cash.

Sub-asset allocation within classes, such as domestic and non-domestic securities or large-, mid- or small-capitalisation equities.

Allocation to indexed or actively managed funds or both.

The importance of rebalancing to maintain a consistent risk profile.

Defining investment goals and constraints

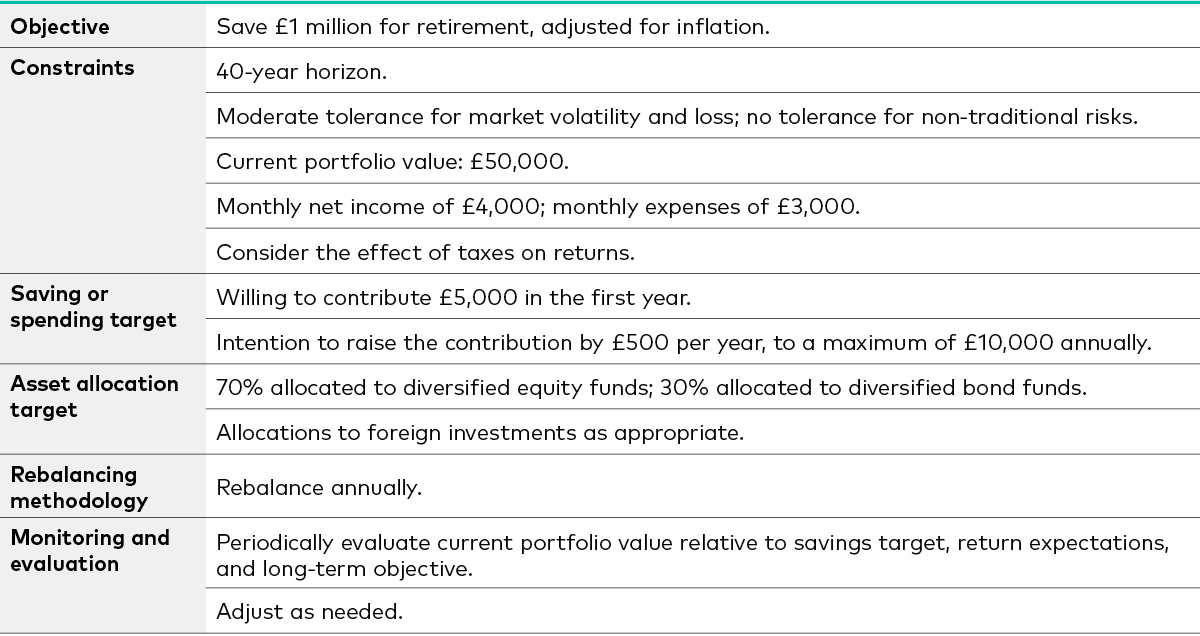

A sound investment plan begins by outlining the investor’s objectives as well as any significant constraints. Because most objectives are long term, the plan should be designed to endure through changing market environments and be flexible enough to adjust for unexpected events. The figure below provides an example of a plan framework.

Most investment objectives can be viewed in the context of a required rate of return (RRR). That is the return a portfolio would need to generate to bridge the gap between an investor’s current assets, any future cash flows and the investment goals. For example, say an investor has determined that they need £1 million in 40 years’ time in today’s money (inflation-adjusted) for a comfortable retirement. If that investor starts today by depositing £10,000 and saves the same inflation-adjusted amount each year over 40 years, the real RRR needed to reach the goal would be 4%.

Example of a basic framework for an investment plan

Notes: This example is hypothetical. It does not represent any real investor and should not be taken as a guide. Depending on an actual investor’s circumstances, such a plan could be expanded or consolidated. For example, many financial advisers may find value in outlining the investment strategy—that is, specifying whether tactical asset allocation will be employed, whether actively or passively managed funds will be used, and the like.

Source: Vanguard.

One primary constraint in meeting any objective is the investor’s tolerance for risk. Time can be another constraint; a shorter time frame allows for different risks than an infinite one. Other constraints can include tax exposure, liquidity requirements and unique limitations such as a desire to avoid certain investments.

The danger of lacking a plan

Without a plan, investors often build their portfolios from the bottom up, focusing on investments piecemeal rather than on how the portfolio as a whole is serving the objective. Another way to characterise this process is ‘fund collecting’. These investors are drawn to evaluate a particular fund, and if it seems attractive, they buy it – often without thinking about how or where it may fit within the overall allocation.

A sound investment plan can help the investor avoid such behaviour, because it demonstrates the purpose and value of asset allocation, diversification and rebalancing. It also helps the investor stay focused on intended contribution and spending rates.

Broad strategic asset allocation

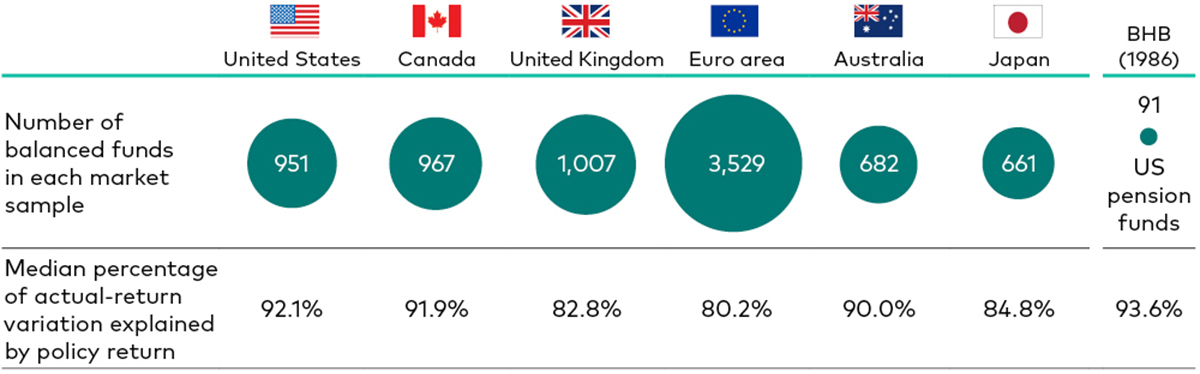

When developing a portfolio, it is critical to select a combination of assets that offers the best chance of meeting the plan’s objective, subject to the investor’s constraints. In portfolios with broadly diversified holdings, the mix of assets will determine both the aggregate returns and their variability. A seminal 1986 study by Brinson, Hood, and Beebower showed that the asset allocation decision was responsible for the vast majority of a diversified portfolio’s return patterns over time. These findings were confirmed by Vanguard’s own study in 2020 and other research, including Ibbotson and Kaplan (2000)1, suggesting that a portfolio’s investment policy is an important contributor to return variability.

Our analytical framework, shown below, covers the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia and Japan from 1 January 1990, and the euro area from 1 January 1999, to 30 September 2020. This research confirms our earlier conclusions that, over time and on average, most of the return variability of a broadly diversified portfolio that engages in limited market timing is due to its underlying static asset allocation.

Role of asset allocation policy in return variation of balanced funds

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future returns.

Notes: For each fund in our sample, a calculated adjusted R2 represented the percentage of actual-return variation explained by policy-return variation. Percentages shown in the figure—92.1% for the US, 91.9% for Canada, 82.8% for the United Kingdom, 80.2% for the euro area, 90.0% for Australia, and 84.8% for Japan—represent the median observation from the distribution of percentage of return variation explained by asset allocation for balanced funds. For the period January 1990–September 2020, the sample included: for the US, 951 balanced funds; for Canada, 967; for the UK, 1007; for Australia, 682; and for Japan, 661. For the euro area, the sample included 3,529 balanced funds—domiciled in Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain—for the period January 1999–September 2020. Calculations were based on monthly net returns, and policy allocations were derived from a fund’s actual performance compared with a benchmark using returns-based style analysis (as developed by William F. Sharpe) on a 36-month rolling basis. Funds were selected from Morningstar’s Multi-Sector Balanced category. Only funds with at least 48 months of return history were considered in the analysis. The policy portfolio was assumed to have a US expense ratio of 1.5 basis points per month (18 bps annually, or 0.18%) and a non-US expense ratio of 2.0 bps per month (24 bps annually, or 0.24%).

Sources: Vanguard calculations, using data from Morningstar, Inc.

Active investment decisions such as market timing and security selection had relatively little impact on return variability over time. In addition, we found that market capitalisation-weighted indexed policy portfolios provided higher returns and lower volatility than the average actively managed fund. We also found that those funds that were able to generate positive alpha tended to share two characteristics: larger average assets and lower costs.

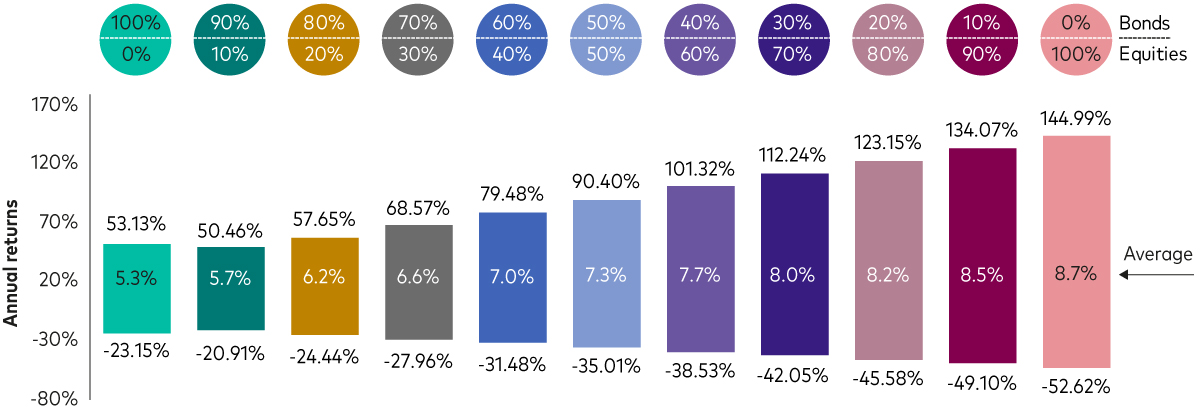

Risk and return

An informed understanding of the risk and return characteristics of the various asset classes is vital to the portfolio construction process. The chart below shows a simple example of this relationship, using two asset classes (global stocks and global bonds) to demonstrate the impact of broad asset allocation on returns and their variability. Although the average annual returns represent averages over 120 years and should not be expected in any given year or time period, they provide an idea of the long-term historical returns and downside market risk that have been associated with various allocations.

The mixture of assets defines the spectrum of returns

*Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. *

Notes: Reflects the maximum and minimum calendar year returns, along with the average annualised return, from 1901-2022, for various stock and bond allocations, rebalanced annually. Equities are represented by the DMS UK Equity Total Return Index from 1901 to 1969; thereafter, equities are represented by the MSCI UK. Bond returns are represented by the DMS UK Bond Total Return Index from 1901 – 1985; the FTSE UK Government Index from Jan 1986 – Dec 2000 and the Bloomberg Barclays Sterling Aggregate thereafter. Returns are in sterling, with income reinvested, to 31 December 2022.

Source: Vanguard.

The risk and return trade-off should be a primary consideration when determining one’s strategic asset allocation. For example, the hypothetical investor described earlier, who is saving for retirement with a 4% real RRR, should select an asset mix that meets or exceeds that amount, with an acceptable corresponding risk of potential loss. If either of those requirements is not met, the investor may need to revisit them. Of course, shorter time horizons may require investing more in bonds and cash, which have less downside volatility, than in equities.

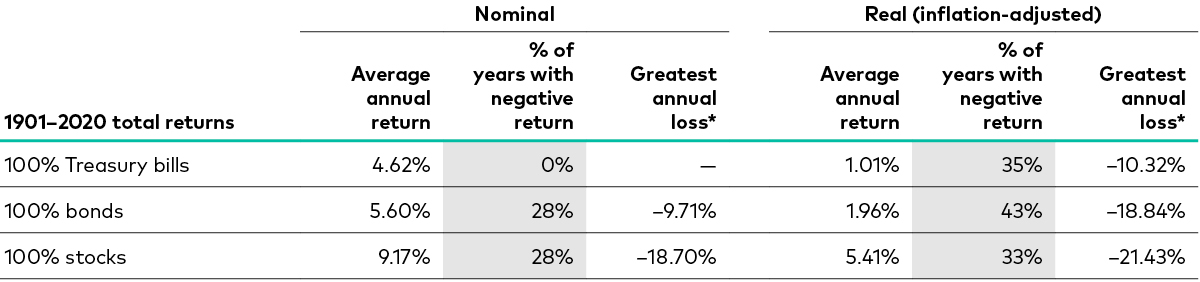

Inflation risk is often overlooked and can have a major effect on asset-class returns, changing the portfolio’s risk profile. This is one reason why Vanguard generally does not believe that cash plays a significant role in a diversified portfolio with long investment horizons. Rather, cash should be used to meet liquidity needs or be integrated into a portfolio designed for shorter horizons.

The figure below shows the long-term historical returns of global stocks, bonds and cash on both a nominal and inflation-adjusted basis. Returns are measured in GBP and include the reinvestment of dividends and income. As highlighted, inflation can be particularly damaging over longer periods, as its effects compound over time.

Trade-off between market risk and inflation risk

Notes: Data cover 31 December 1900 to 31 December 2020. Returns are in local currency. Nominal value is the return before adjustment for inflation; real value includes the effect of inflation.

Sources: Vanguard, using Dimson-Marsh-Staunton global returns data from Morningstar, Inc. using the DMS UK Equity Index and the DMS UK Bond Index.

Sub-asset allocation

Once the appropriate strategic asset allocation has been determined between riskier assets (equities) and less risky ones (fixed income), the focus should turn to diversification within these asset classes to reduce exposure to risks associated with a particular region, company, sector or market segment.

Domestic and non-domestic equities and bonds

Investors seeking exposure to stock and bond markets must decide on the degree of exposure to the various risk and return characteristics appropriate for their objectives. For equities, in addition to domestic and non-domestic exposure, attributes include market capitalisation (large, mid, and small) and style (growth and value). For bonds, attributes include duration (short, intermediate or long-term maturities), credit quality (high, medium or low), corporate versus sovereign debt and inflation-protected issues. Each category can have specific risk factors.

Owning a portfolio with at least some exposure to many or all key market components ensures the investor will have some participation in stronger areas while also mitigating the impact of weaker areas at any given time. Vanguard believes that gaining exposure to these asset classes through a market-cap-weighted portfolio that matches the risk-return profile of the asset-class target through broad diversification is a valuable starting point for many investors. We also recognise that this is not a one-size-fits-all solution and that others are appropriate depending on an investor’s goals and, more importantly, ability to take on active or model risk.

Broad-market index funds are one way to achieve market cap weighting within an asset class. For equities, relevant information is continuously incorporated into stock prices through investor trading, which then affects market capitalisation. Market-cap weighted indices therefore reflect the consensus investor estimate of each company’s relative value. For bonds, exposure to nominal investment-grade bond segments through a total bond market fund would achieve the goals of both market proportionality to those segments and similar average duration to the broad market.

A primary way to diversify is through non-domestic investing. To the extent a broadly diversified market-cap-weighted index fund is a valuable starting point, it could well follow that using a global market-cap-weighted fund is a reasonable default for investors. However, we find that investors tend to own more equity and more fixed income assets of their resident country than the market-cap weighting would suggest. For example, as at 31 December 2020, UK equities accounted for 5% of the global equity market yet UK investors collectively held 19% in domestic equities at the end of 2020. This situation was similar in each country we analysed.

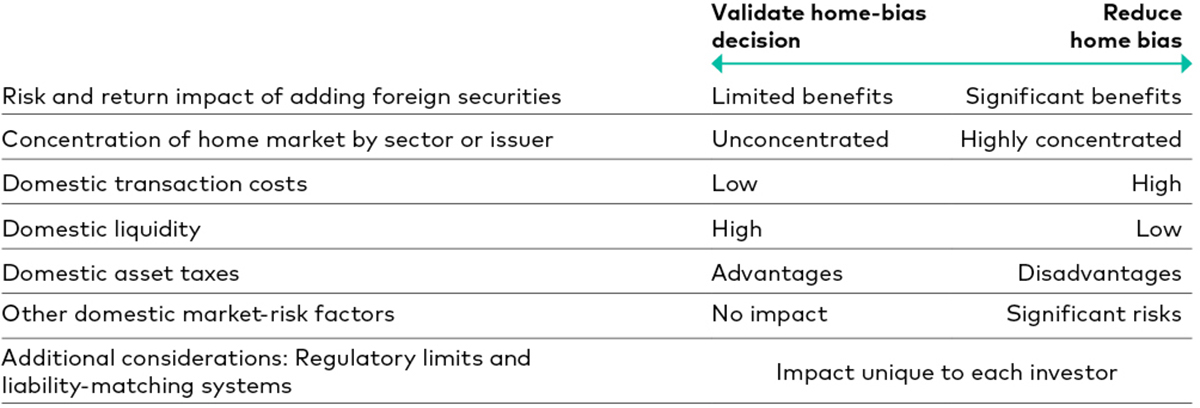

When portfolio bias is a conscious decision, it is typically made for one of two reasons: return expectations or risk mitigation. Our framework highlighted below helps to determine the validity of home bias depending on individual circumstances.

Factors affecting the decision to invest in foreign assets

Source: Vanguard.

In determining the right mix of domestic and international equity and fixed income, a number of factors should be evaluated, such as worldwide market cap, asset classes’ expected returns, volatilities, correlations and costs. For many investors, the tax treatment of foreign relative to domestic assets can be significant. We believe in balancing these factors with the additional diversification benefits that are achieved.

Another necessary decision is whether to hedge non-domestic currency exposure. It is a reasonable forward-looking assumption that over extended time horizons, the gross returns will be similar between a hedged and unhedged investment. Whether to hedge equity currency exposure should be based on risk and diversification effects, not on return, for those investors willing to tolerate a modest return drag from hedging. Factors that influence this decision include the availability of a low-cost hedging programme or hedged product, a smaller domestic allocation resulting in greater currency exposure, a belief that foreign currency is unlikely to be a diversifier in the local market and a portfolio objective specifically targeting volatility. Currency fluctuations account for a significant portion of the volatility in international bonds. For this reason, Vanguard recommends hedging currency exposure to decrease risk and mitigate this volatility.

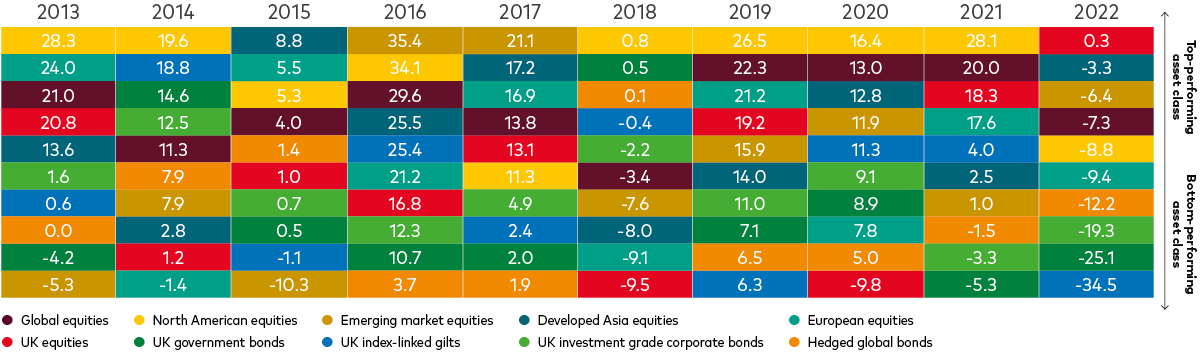

Often, investors try to determine the sub-asset allocations of their portfolio by looking at outperformance; however, relative performance changes often. Over very long-term horizons, most sub-asset classes tend to perform in line with their broad asset class, but, over short periods, there can be large differences. The graphic below shows examples of annual returns for various asset and sub-asset classes.

There is little persistence in asset class performance

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

Source: Vanguard calculations, data from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2022, using data from Barclays Capital and Thomson Reuters Datastream and FactSet. Global equities as the FTSE All-World Index, North American equities as the FTSE World North America Index, Emerging market equities as the FTSE All-World Emerging Index, Developed Asia equities as the FTSE All World Developed Asia Pacific Index, European equities as the FTSE All World Europe ex-UK Index, UK equities is defined as the FTSE All-Share Index, UK government bonds as Bloomberg Sterling Gilt Index, UK index-linked gilts as Bloomberg UK Govt Inflation-Linked UK Index, UK investment grade corporate bonds as Bloomberg Sterling Aggregate Non-Gilts – Corporate Index, Hedged global bonds as Bloomberg Global Aggregate Index (hedged in GBP). Performance shown is cumulative and denominated in GBP. It includes the reinvestment of all dividends and any capital gains distributions. The performance data does not take account of the commissions and costs incurred in the issue and redemption of shares.

Non-traditional asset classes

Non-traditional and alternative asset classes and investment strategies include real estate, commodities, private equity, emerging-market bonds and currencies. Among the alternative strategies sometimes included are long/short and market-neutral approaches. Each of these can offer advantages compared with investing in traditional stocks, bonds and cash, including:

- Potentially higher expected returns.

- Lower expected correlation and volatility vis-à-vis traditional market forces.

- The opportunity to benefit from market inefficiencies through skill-based strategies.

These potential advantages are often debated, and assessing the degree to which they can be relied on can be difficult. This is even more evident for strategies in which investable beta is not available. Strategies such as long/short, market neutral and private equity largely depend on manager skill; success will therefore depend on consistently selecting the best-performing managers. One downside to all these non-traditional asset classes is their potential to be very expensive relative to traditional investments in equities and bonds.

Active and passive strategies

Market-cap-weighted index investing is a valuable starting point for many investors. It can be delivered inexpensively and provides exposure to the broad market while offering diversification and transparency. Yet for investors looking for the opportunity to outperform a target benchmark, an actively managed portfolio strategy can be appealing. Despite the debate about whether active or index investing is better, both strategies have distinct benefits and trade-offs.

With the use of an active manager, selection is critical to success. The active management universe varies widely, and successfully choosing a manager that will outperform in the future is difficult. Focusing on the advisory firm and its people, philosophy and process can help in the search for a skilled manager. One downside to all these non-traditional asset classes is their potential to be very expensive relative to traditional investments in equities and bonds. Ultimately, identifying talent, choosing low-cost investments and staying patient are important to succeeding with active management.

Because both index investing and low-cost active management have potential advantages, combining these approaches can prove effective. As indexing is incrementally added to active management strategies, a portfolio’s risk characteristics converge closer to those of the benchmark, decreasing tracking error and providing diversification. The combination offers the opportunity to outperform while adding some risk control relative to the benchmark. The appropriate mix should be determined by the goals, active risk tolerance and objectives of the investment policy statement, keeping in mind the trade-off between tracking error and the possibility of outperformance.

Although the active/passive question is a consideration for many investors, establishing an appropriate asset allocation is the first and most important step in the portfolio construction process.

Rebalancing

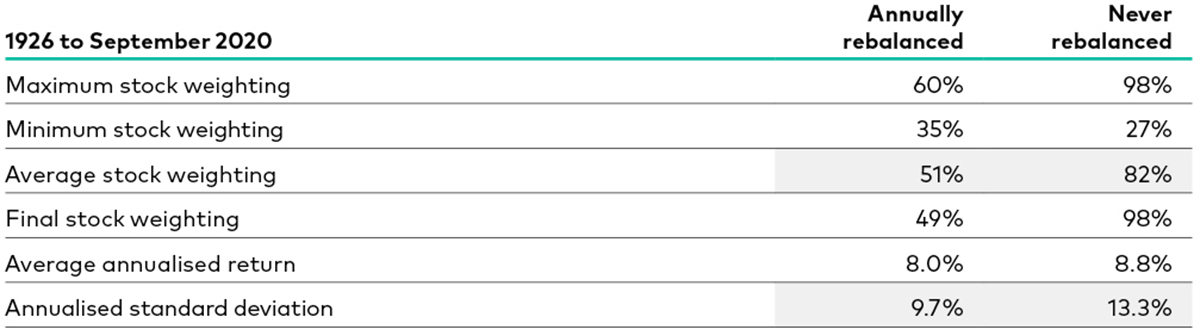

Over time, as a portfolio’s investments produce different returns, the portfolio is likely to drift from its target asset allocation. The table below shows that, over a long horizon, the equity allocation of a 50/50 globally diversified portfolio that is never rebalanced drifts upwards significantly, to 98%. The portfolio also acquires risk-and-return characteristics that may be inconsistent with the investor’s goals and preferences. In the example shown, the portfolio produces a slightly higher return, but its volatility increases significantly, from 9.7% to 13.3%.

Comparing a 50/50 rebalanced portfolio with a 50/50 never-rebalanced portfolio

Notes: This table does not represent the returns of any particular investment.

It assumes a portfolio of 50% global stocks and 50% global bonds, with all returns in nominal US dollars. It also assumes that no new contributions or withdrawals were made, that dividend payments were reinvested in equities, that interest payments were reinvested in bonds, and that there were no new taxes. All statistics are annualised. Stocks are represented by the Standard & Poor’s 90 Index from 1926 to 3 March 1957; the S&P 500 Index from 4 March 1957, to 1969; the MSCI World Index from 1970 to 1987; the MSCI All Country World Index from 1988 to 31 May 1994; and the MSCI All Country World Investable Market Index from 1 June 1994 to 30 September 2020. Bonds are represented by the S&P High Grade Corporate Index from 1926 to 1968, the Citigroup High Grade Index from 1969 to 1972, the Lehman Long-Term AA Corporate Index from 1973 to 1975, the Barclays US Aggregate Bond Index from 1976 to 1989, and the Barclays Global Aggregate Bond Index (USD Hedged) from 1990 to 30 September 2020.

Sources: Vanguard calculations, based on data from FactSet.

How frequently the portfolio should be monitored, how far an asset allocation should be allowed to deviate from its target before it is rebalanced, and whether periodic rebalancing should be used are common questions. Although each of these decisions affects a portfolio’s risk-and-return characteristics, the differences in risk-adjusted returns are not very significant. Thus, the answers to “how often, how far and how much” are mostly down to investor preference.

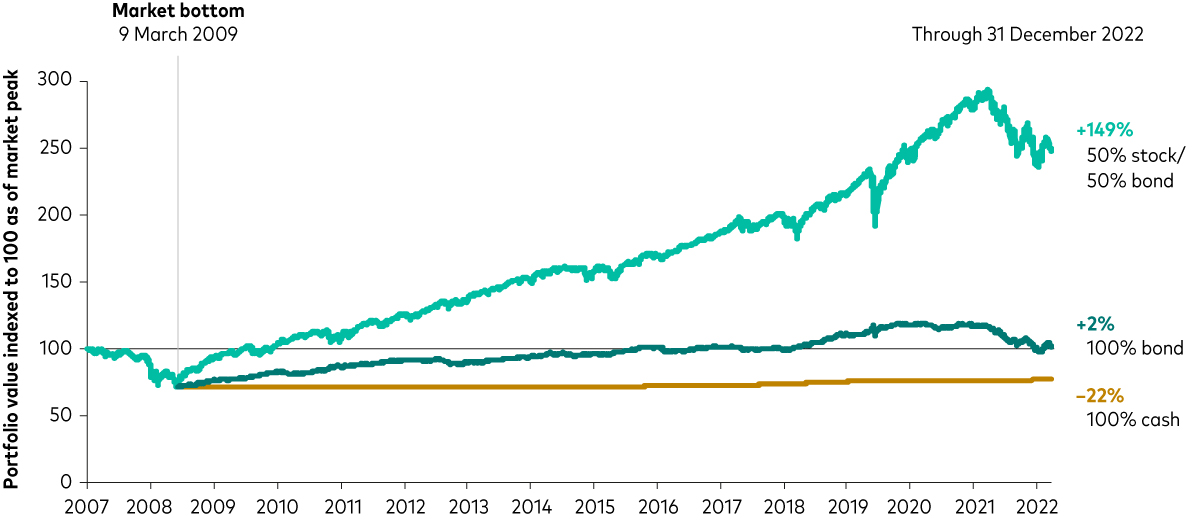

Failure to rebalance can increase an investor's exposure to risk

The performance of an index is not an exact representation of any particular investment, as you cannot directly invest in an index.

Sources: Vanguard calculations, based on data from FactSet. As of December 31, 2022.

Notes: US stocks represented by S&P 500 Index. US bonds represented by Bloomberg Barclays US Aggregate Index. Cash represented by Bloomberg Barclays US 3-Month Treasury Bellwether Index.

A quantitative model-based approach to portfolio construction

We have established that consideration should be given to an investor’s goals, risk aversion and expected asset returns, correlations and volatility. But is there a quantitative way to determine asset allocation?

Vanguard’s proprietary quantitative asset allocating framework, the Vanguard Asset Allocation Model (VAAM), does exactly that, and more. Asset return distributions are generated by our asset simulation model, the Vanguard Capital Markets Model (VCMM), while the VAAM optimises asset allocation based on several inputs such as expected return, risk, goals, constraints and risk preferences.

The VAAM can help allocate to different types of assets (active, index and illiquid investment vehicles) in a conceptually rigorous fashion. Here, the expected return of the optimal portfolio can be assessed against the RRR to determine feasibility toward the investor’s goals. There is no one-size-fits-all portfolio or recommendation under this construct, which makes the VAAM ideal for the application of personalised advice.

Such a process for portfolio construction requires one to take on active risk. However, it can be mitigated by embedding reasonable allocation constraints that support the broader diversification principles discussed throughout this article.

A few key advantages of the VAAM methodology are:

The VAAM process for portfolio construction explicitly accounts for risk, return and an investor’s risk tolerance.

VAAM-based asset allocations strategically account for the prevailing environment and form suitable long-term-oriented portfolios that target an investor’s goals (RRR) and risk preferences.

The VAAM allows for systematically allocating between passive, active and illiquid assets to increase a portfolio’s expected returns. By design, it overcomes issues inherent in traditional models that do not account for an investor’s aversion toward active risk and make rebalancing assumptions that are not appropriate for illiquid assets.

Based on a total-return approach, the VAAM can help form income-oriented portfolios, tax-aware portfolios and environmental, social and governance (ESG) portfolios under a rigorous and consistent portfolio framework.

Vanguard’s multi-asset solutions are built on the expertise of VCMM and VAAM, using low-cost Vanguard index funds to implement the specific allocation derived from the VAAM model.

To find out more about multi-asset investing, read Why buy a multi-asset solution?

This is a summary of Vanguard’s Framework for Constructing Globally Diversified Portfolios by Scott J Donaldson, Harshdeep Ahluwalia, Giulio Renzi-Ricci, Victor Zhu and Alexander Aleksandrovich, published in June 2021. The paper updates an early version published in 2017, which succeeded a 2013 paper Vanguard’s Framework for Constructing Diversified Portfolios. All papers are based on Vanguard research first published in 2007 as Portfolio Construction for Taxable Investors by Scott J Donaldson and Frank J Ambrosio.

1 Ibbotson, Roger G., and Paul D. Kaplan, 2000. Does Asset Allocation Policy Explain 40, 90, or 100 Percent of Performance? Financial Analysts Journal 56(1): 26–33.

If you have completed all content in the module, you are ready to take the quiz and collect your CPD

Ready to test your knowledge?

Take the quizOther Vanguard 365 pillars

Client relationships

CPD content crafted to empower you to service your client’s needs effectively, build relationships, create loyalty and achieve new business growth.

Practice management

CPD content designed to help you build your practice, market your services effectively and cultivate a thriving professional network.

Financial planning

CPD content structured to give you access to useful tools, guides and multimedia resources covering diverse topics from risk profiling to retirement planning.

Investment risk information

The value of investments, and the income from them, may fall or rise and investors may get back less than they invested.

Important information

This article is designed for use by, and is directed only at persons resident in the UK.

The information contained in this article is not to be regarded as an offer to buy or sell or the solicitation of any offer to buy or sell securities in any jurisdiction where such an offer or solicitation is against the law, or to anyone to whom it is unlawful to make such an offer or solicitation, or if the person making the offer or solicitation is not qualified to do so. The information in this document does not constitute legal, tax, or investment advice. You must not, therefore, rely on the content of this article when making any investment decisions.

The information contained in this article is for educational purposes only and is not a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell investments.

© 2025 Vanguard Asset Management, Limited. All rights reserved.

Vanguard Asset Management, Limited is authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority.